If you were paying very close attention last week, you’ll have noticed my attempt to come up with an estimate of π, geometrically, as part of The Aperiodical’s π Day challenge (even if it’s not really π Day):

Oo, my second effort at estimating π came to 3.14151, correct to 0.003%! cc @aperiodical pic.twitter.com/2vuvys0mka

— Colin Beveridge (@icecolbeveridge) March 10, 2015

Viewed on its own, that’s probably a bit mysterious, so I thought I’d write a little article to explain what was going on, and explore some of the maths behind it.

The approximation

The first thing I did, after watching the video, was think about (read: Google) what other strategies one might use to approximate π. I thought about measuring a cylinder (too much work); I thought about something to do with the Catalan numbers (would involve research); and I finally settled on a geometric method that relies on a cool almost-identity:

\[x \approx \frac{3 \sin(x)}{2 + \cos(x)} \]

There are two immediate questions:

- Why does that work?

and - How does it help?

Why it works is fairly simple: a good approximation for $\sin(x)$ is $x – \frac{1}{6}x^3 + \frac{1}{120}x^5 – …$, and a good approximation for $\cos(x)$ is $1 – \frac{1}{2}x^2+ \frac{1}{24}x^4 – …$. That means the fraction becomes:

\[ \frac{x\left(3 – \frac{1}{2}x^2 + \frac{1}{40}x^4 – …\right)}{3 – \frac{1}{2}x^2 + \frac{1}{24}x^4 – …} \]

Ignoring the $x$, the rest of the numerator and denominator only differ in the $x^4$ term (and onward), which, for a small angle, makes for a very small error.

How does it help? Well, sine and cosine are circular functions, which means they can be measured off of a circle. Given a pair of perpendicular axes and a circle centred on them, any point on the circumference is $R \sin(\theta)$ above the horizontal axis and $R \cos(\theta)$ to the right of the vertical axis, assuming the circle has radius $R$ and the point forms an angle $\theta$ with the horizontal axis.

That means, if you construct an angle of, say, $\frac{\pi}{6}$, you should be able to construct and measure $\frac{3R \sin(\theta)}{2R + R\cos(\theta)}$, which is approximately $\theta$.

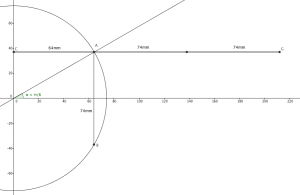

The picture

A proper version. Chord AB has length 74mm, and the perpendicular ray CG has length 212mm. (Click to enlarge)

So, I drew that kind of circle. I constructed perpendiculars. I extended lines. I measured them. And I did some simplification.

If I wanted an estimate for π, I’d need to multiply everything by 6; meanwhile, I’d measured double $R\sin(\theta)$, the chord of the circle (AB in the diagram), so I’d need to multiply that number — 74mm — by 9 to get 666. Oooo!

On the bottom, I’d extended my horizontal chord (CA) by two radii to get $2R + R\cos(\theta)$, which I measured to be 212mm (CG). Then I did some tedious long division to get 3.14151, which isn’t bad for something knocked up on the sofa with a borrowed geometry kit. It’s almost too good to be true.

Well, yes, of course I cheated

Estimates of π that are good to nearly five significant figures don’t pop off of such pages, at least, not without a great deal of preparation. For example, an unscrupulous geometer might fire up Desmos, draw the line $y = \pi x$, and see where it falls unusually close to a lattice point. (Better mathematicians than me would use a continued fraction to get the best estimate possible — although I did consider $\frac{355}{113}$, I couldn’t make it look natural. That was my first attempt.)

I found that $\frac{333}{106}$ was pretty much bang on the money — certainly, good enough for this. However, I needed the top to be a multiple of 18; it’s already a multiple of 9, so doubling it would work. I also know that $\sin\left(\frac {\pi}{6}\right) = \frac{1}{2}$, giving me a radius of $\frac{666}{18} = 74\text{mm}$.

From there, all that remained to do was fudge the horizontal chord marks ever so slightly so they coincided with the 212mm I’d pre-measured, and boom! A natural-looking, but ever-so-good estimate of π.