In Part I of this series of posts, I introduced the sporadic groups, finite groups of symmetries which aren’t the symmetries of any obvious categories of shapes. The sporadic groups in turn are classified into the Happy Family, headed by the Monster group, and the Pariahs. In Part II, I discussed Monstrous Moonshine, the connection between the Monster group and a type of function called a modular form. This in turn ties the Monster group, and with it the Happy Family, to elliptic curves, Fermat’s Last Theorem, and string theory, among other things. But until 2017, the Pariah groups remained stubbornly outside these connections.

In September 2017, John Duncan, Michael Mertens, and Ken Ono published a paper announcing a connection between the Pariah group known as the O’Nan group (after Michael O’Nan, who discovered it in 1976) and another modular form. Like Monstrous Moonshine, the new connection is through an infinite-dimensional shape which breaks up into finite-dimensional pieces. Also like Monstrous Moonshine, the modular form in question has a deep connection with elliptic curves. In this case, however, the connection is more subtle and leads through yet another set of important mathematical objects: the quadratic fields.

At play in the fields quadratic

It’s also possible to have fields of things that aren’t numbers, which are useful in lots of other situations — see Section 4.5 of The Mathematics of Secrets for a cryptographic example.

What mathematicians call a field is a set of objects which are closed under addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division (except division by zero). The rational numbers form a field, and so do the real numbers and the complex numbers. The integers don’t form a field because they aren’t closed under division, and the positive real numbers don’t form a field because they aren’t closed under subtraction.

A common way to make a new field is to take a known field and enlarge it a bit. For example, if you start with the real numbers and enlarge them by including the number $i$ (the square root of $-1$), then you also have to include all of the imaginary numbers, which are multiples of $i$, and then all of the numbers which are real numbers plus imaginary numbers, which gets you the complex numbers. Or you could start with the rational numbers, include the square root of $2$, and then you have to include the numbers that are rational multiples of the square root of $2$, and then the numbers which are rational numbers plus the multiples of the square root of $2$. Then you get to stop, because if you multiply two of those numbers you get

\[ (a+b\sqrt{2})(c+d\sqrt{2}) = (ac + 2bd) + (ad+bc)\sqrt{2} \]

which is another number of the same form. Likewise, if you divide two numbers of this form, you can rationalize the denominator and get another number of the same form. We call the resulting field the rational numbers “adjoined with” the square root of $2$. Fields which are obtained by starting with the rational numbers and adjoining the square root of a rational number (positive or negative) are called quadratic fields.

Identifying a quadratic field is almost, but not quite, as easy as identifying the square root you are adjoining. For instance, consider adjoining the square root of $8$. The square root of $8$ is twice the square root of $2$, so if you adjoin the square root of $2$ you get the square root of $8$ for free. And since you can also divide by $2$, if you adjoin the square root of $8$ you get the square root of $2$ for free. So these two square roots give you the same field.

This is the same $b^2 – 4ac$ as in the quadratic formula.

For technical reasons, a quadratic field is identified by taking all of the integers whose square roots would give you that field, and picking out the integer $D$ with the smallest absolute value that can be written in the form $b^2 – 4ac$ for integers $a$, $b$ and $c$. This number $D$ is called the fundamental discriminant of the field. So, for example, $8$ is the fundamental discriminant of the quadratic field we’ve been talking about, not $2$, because $8 = 4^2 – 4 \times 2 \times 1$, but $2$ can’t be written in that form.

Prime suspects

After addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, one of the really important things you can do with rational numbers is factor their numerators and denominators into primes. In fact, you can do it uniquely, aside from the order of the factors. If you have number in a quadratic field, you can still factor it into primes, but the primes might not be unique. For example, in the rational numbers adjoined with the square root of negative 5 we have

\[ 6 = 2 \times 3 = (1+\sqrt{-5})(1-\sqrt{-5}) \]

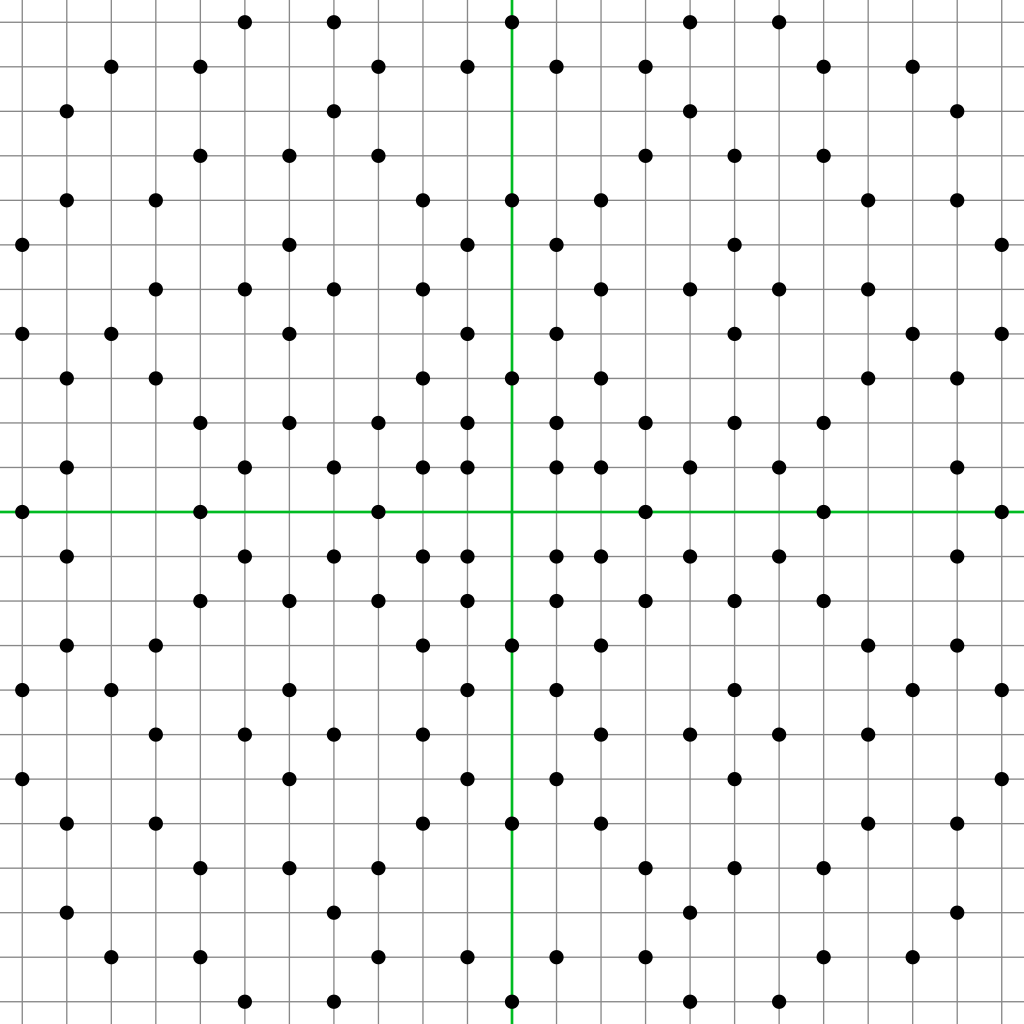

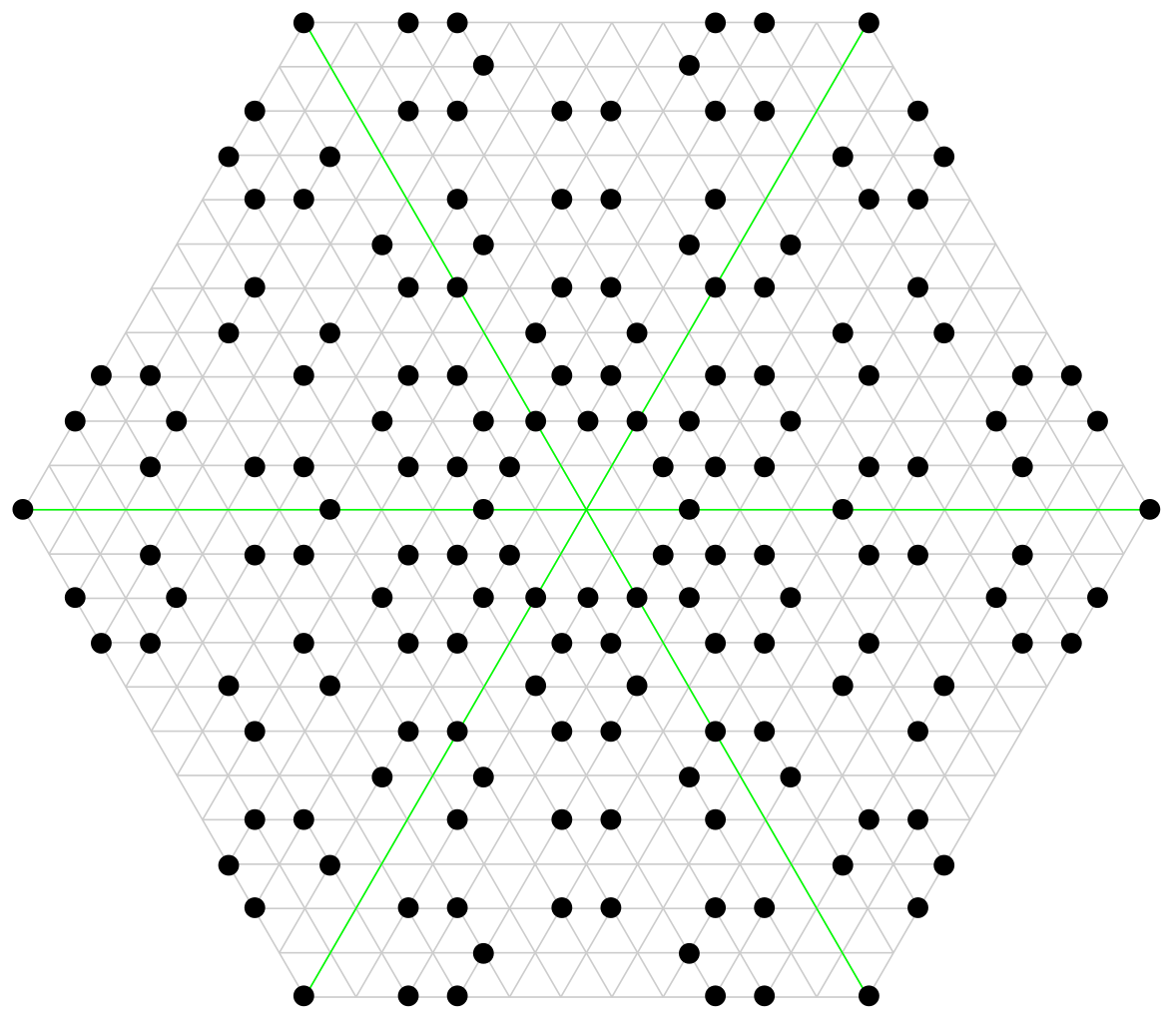

where $2$, $5$, $1+\sqrt{-5}$, and $1-\sqrt{-5}$ are all primes. You’ll have to trust me on that last part, since it’s not always obvious which numbers in a quadratic field are prime. Figures 1 and 2 show some small primes in the rational numbers adjoined with the square roots of negative 1 and negative 3, respectively, plotted as points in the complex plane.

- Figure 1. Some small primes in the rational numbers adjoined with the square root of -1 (D = -4), plotted as points in the complex plane. By Wikimedia Commons User Georg-Johann.)

- Figure 2. Some small primes in the rational numbers adjoined with the square root of -3 (D = -3), plotted as points in the complex plane. By Wikimedia Commons User Fropuff.)

We express this by saying the rational numbers have unique factorization, but not all quadratic fields do. The question of which quadratic fields have unique factorization is an important open problem in general. For negative fundamental discriminants, we know that $D = -3, -4, -7, -8, -11, -19, -43, -67, -163$ are the only such quadratic fields; an equivalent form of this was conjectured by Gauss but fully acceptable proofs were not given until 1966 by Alan Baker and 1967 by Harold Stark. For positive fundamental discriminants, Gauss conjectured that there were infinitely many quadratic fields with unique factorization but this is still unproved.

Furthermore, Gauss identified a number, called the class number, which in some sense measures how far from unique factorization a field is. If the class number is $1$, the field has unique factorization, otherwise not. The rational numbers adjoined with the square root of negative $5$ ($D = -20$) have class number $2$, and therefore do not have unique factorization. Gauss also conjectured that the class number of a quadratic field went to infinity as its discriminant went to negative infinity; this was proved by Hans Heilbronn in 1934.

Moonshine with class (numbers)

What about Moonshine? Duncan, Mertens, and Ono proved that the O’Nan group was associated with the modular form

\[ F(z) = e^{-8 \pi i z} + 2 + 26752 e^{6 \pi i z} + 143376 e^{8 \pi i z} + 8288256 e^{14 \pi i z} + \ldots \]

which has the property that the coefficient of $e^{2|D| \pi i z}$ is related to the class number of the field with fundamental discriminant $D \lt 0$. Furthermore, looking at elements of the O’Nan group sometimes gives us very specific relationships between the coefficients and the class number.

Mathematicians say a symmetry that gets you back where you started after you do it $n$ times is a “symmetry of order $n$”.

For example, the O’Nan group includes a symmetry which is like a 180 degree rotation, in that if you do it twice you get back to where you started. Using that symmetry, Duncan, Mertens, and Ono showed that for even $D \lt -8$, $16$ always divides $a(D) + 24h(D)$, where $a(D)$ is the coefficient of $e^{2|D|\pi i z}$ and $h(D)$ is the class number of the field with fundamental discriminant D. For the example $D = -20$ from above, $a(D) = 798588584512$ and $h(D) = 2$, and $16$ does in fact divide $798588584512 + 48$. Similarly, other elements of the O’Nan group show that $9$ always divides $a(D)+24h(D)$ if $D = 3k+2$ for some integer $k$ and that $5$ and $7$ always divide $a(D)+24h(D)$ under other similar conditions on $D$. And $11$ and $19$ divide $a(D)+24h(D)$ under (much) more complicated conditions related to points on an elliptic curve associated with each $D$, which brings us back nicely to the connection between Moonshine and elliptic curves.

How much Moonshine is out there?

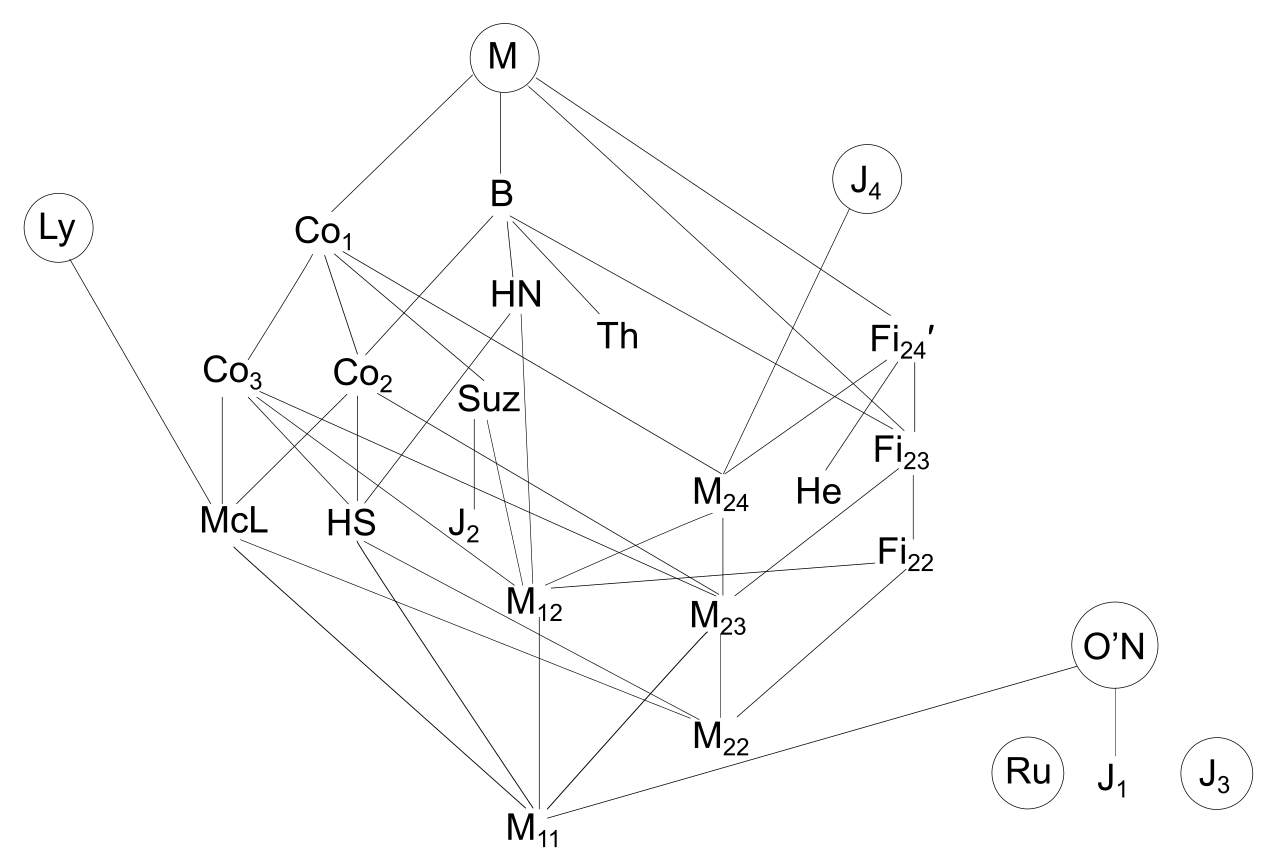

Monstrous Moonshine showed that the Monster, and therefore the Happy Family, was related to modular forms and elliptic curves, as well as string theory. O’Nan Moonshine brings in two more sporadic groups, the O’Nan group and its subgroup the “first Janko group”. (Figure 3 shows the connections between the sporadic groups. “M” is the Monster group, “O’N” is the O’Nan group, and “J1” is the first Janko group.) It also connects the sporadic groups not just to modular forms and elliptic curves, but also to quadratic fields, primes, and class numbers. Furthermore, the modular form used in Monstrous Moonshine is “weight 0”, meaning that $k = 0$ in the definition of a modular form given in Part II. That ties this modular form very closely to elliptic curves.

- Figure 3. Connections between the sporadic groups. Lines indicate that the lower group is a subgroup or a quotient of a subgroup of the upper group. “M” is the Monster group and “O’N” is the O’Nan group; the groups connected below the Monster group are the rest of the Happy Family. (By Wikimedia Commons User Drschawrz.)

Umbral Moonshine also uses weight $3/2$ modular forms.

The modular form in O’Nan Moonshine is “weight $3/2$”. Weight $3/2$ modular forms are less closely tied to elliptic curves, but are tied to yet more ideas in mathematical physics, like higher-dimensional generalizations of strings called “branes” and functions that might count the number of states that a black hole can be in.

That still leaves four more pariah groups, and the smart money predicts that Moonshine connections will be found for them, too. But will they come from weight $0$ modular forms, weight $3/2$ modular forms, or yet another type of modular form with yet more connections? Stay tuned! Maybe someday soon there will be a Part IV.