Back in 2008, Chaim Goodman-Strauss and Heidi Burgel, together with the late John Conway, wrote a book called The Symmetries of Things, which covered a range of topics around mathematical symmetry and the symmetries of geometric objects.

Now the first two authors have a new book, The Magic Theorem, due for publication this week. We spoke to Heidi and Chaim about where this book has come from and what it’s about.

What is The Magic Theorem?

The Magic Theorem is John Conway’s Magic Theorem, which sorts out the possibilities for symmetrical patterns on the plane with just a simple arithmetic count: There’s a “cost” to the various kinds of features a symmetrical pattern might have, and the theorem asserts that the planar symmetrical patterns are the ones that cost exactly \$2.

That’s quite a big deal: Like many others, Conway had been looking for a straightforward way to understand planar patterns. Previous approaches to listing these out have a kind of ad hoc feel to them, with a lot of cases to sort through and no real hope of a general understanding. This all changed in the mid-1980’s when John learned of Bill Thurstons’ “orbifold” classification of symmetry types.

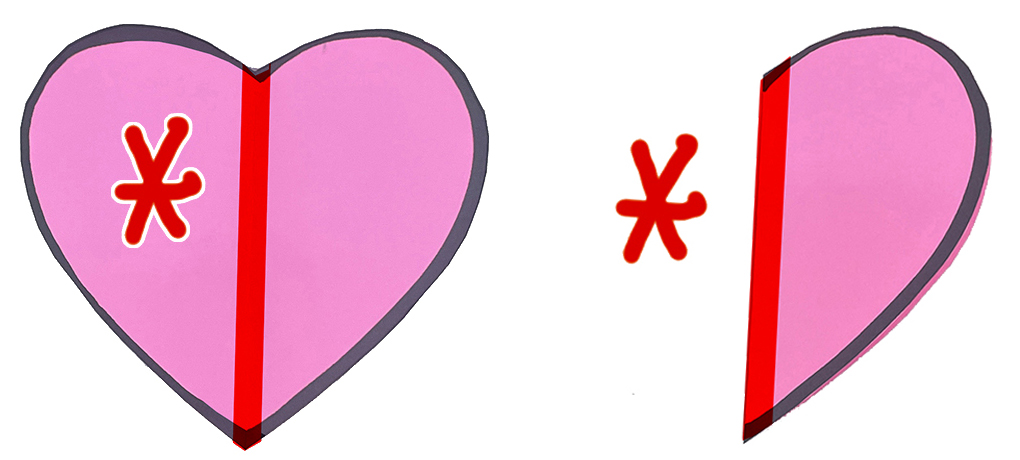

Essentially, Thurston used topology to constrain geometry. Each pattern is associated with a special surface, the pattern’s orbifold, which is created by declaring that points that appear the same in the pattern are to be fused together and henceforth are the same point. For example, the two sides of the heart-shaped pattern below at left are identical (at least ideally). By folding the heart over and fusing identical points together, we have the half-hearted figure at right, the orbifold of the heart-shaped pattern. This orbifold has a newly formed boundary, corresponding to the mirror line down the center of the heart. It is this boundary, a feature of the topology of the orbifold surface, that Conway records with an \(\large \ast\) (a largish asterisk) in his orbifold notation.

The power of this approach comes from the well-understood classification and geometrization of surfaces — the topology and geometry of a surface are tightly bound, each constraining the other. There are only so many options for a surface that has the flat geometry we see in the plane, and these are what the Magic Theorem is counting out. The topological building blocks of an orbifold have a “cost”, and for a planar pattern the cost has to total exactly \$2. There are some number of ways (17 precisely) that this works out. These are the planar symmetry types, named and organized, with a clean proof that they are them.

But this just part of a larger family of Magic Theorems! The spherical symmetrical patterns are those with a cost of less than \$2. More expensive totals give patterns in the hyperbolic plane. Even frieze patterns fit into the scheme. The unity of this approach is really very satisfying.

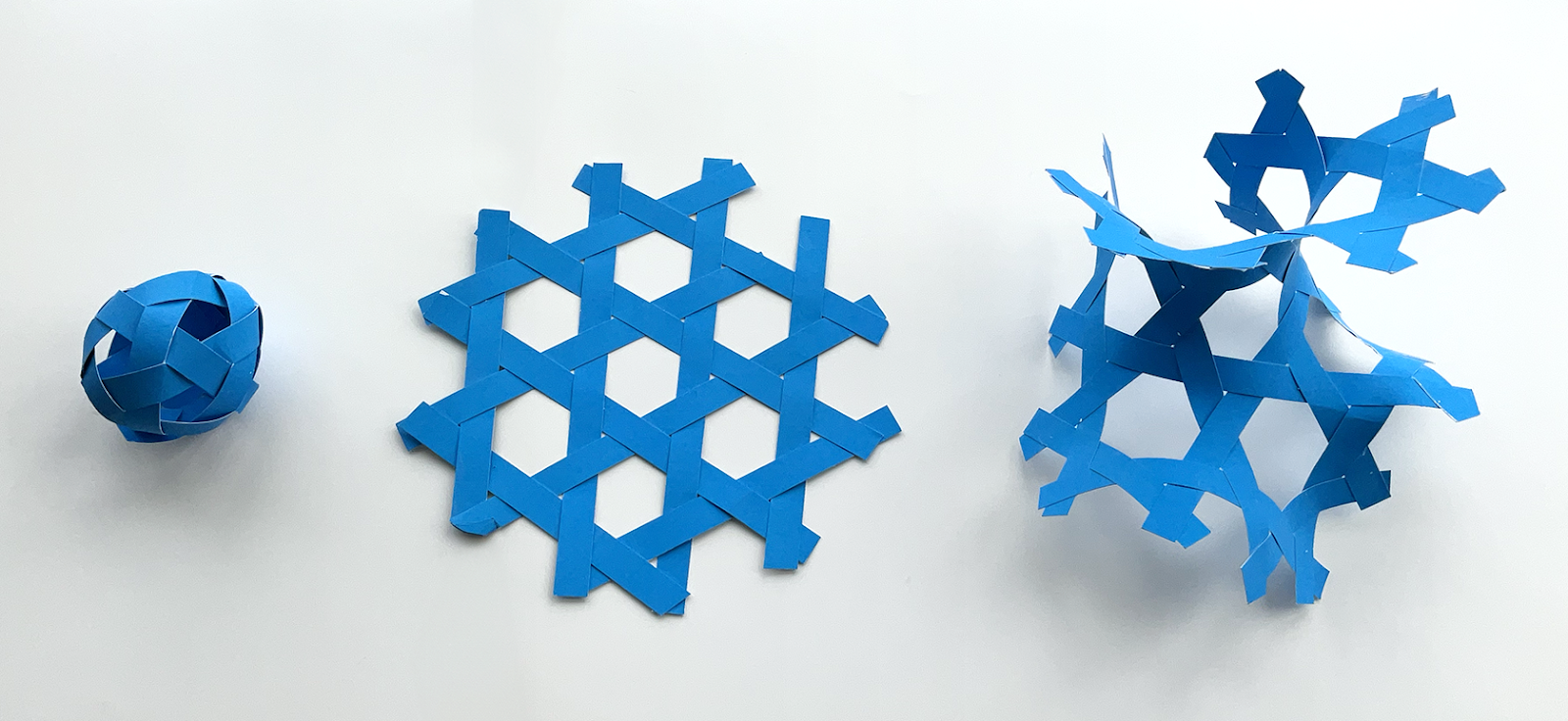

Here’s a picture we like, of three woven patterns, in the geometries of the sphere, plane and hyperbolic plane. Although these patterns are in different kinds of geometry, up close the look the essentially same, triangles arranged around holes. As we take up in the book these patterns’ orbifolds are basically the same too, changing just one parameter (5,6,7).

Upon learning of Thurston’s orbifolds, John devised the orbifold notation and started selling it to the world. Two young graduate students, Heidi and Chaim, came under its spell and began to take up the charge as well, creating our own materials and curricula on this for teachers, outreach, and our own courses. All that was cooking along, and then in late 1999 Heidi approached John and Chaim about writing what became The Symmetries of Things, a definitive account of Conway’s orbifold notation and the Magic Theorem. A mere eight years later, The Symmetries of Things (SoT) appeared.

In this first edition, we were greedy. We had the idea that SoT was going to be for a wide audience, but we just could not help ourselves from putting in lots and lots of other stuff, on color symmetries, technical applications of the orbifold theory, the symmetries of space, and much, much more. The book grew and grew, until we finally had to cut it off. As wonderful as SoT is, it is expensive and encyclopedic — not the lightest introduction to the material.

We always had an intention to prepare a second edition of SoT, but John grew frailer and the list of potential additions grew longer. Finally, we ran out of time: Our dear friend, teacher, mentor, and senior author passed away in April 2020. After this a full new edition seemed overwhelming.

After some months, we realized that we could return to the core of the original book, producing a slimmer, more accessible volume that brings the orbifold theory and its Magic Theorem to a wider audience. We sure had plenty of additional material to include just on that!

What’s new in The Magic Theorem?

The Magic Theorem is really a new book in its own right, aimed to reach as many people as possible. It is Part One of The Symmetries of Things almost doubled in length, with dozens of hands-on things to do and make, real-world examples, and many side discussions. It’s even more thoroughly illustrated, and we are able to showcase wonderful new work that artists have produced since SoT appeared. Every page, we hope, is a real pleasure.

All this, together with dozens of supplemental hands-on teaching materials that are on the book’s website themagictheorem.com And Chaim is excited to finally release his Kaleidesign software, which will allow users to make symmetrical images, like the ones in the book, but from their own photos or even a webcam.

And not insubstantially, The Magic Theorem can be bought at a pretty good price, at least in paperback.

Why did you want to write this new book?

The Symmetries of Things initially aimed to introduce orbifold theory to a wide audience, showcase its power, and encourage its application, but in the end it contained a great deal more. This book aims to share the Magic Theorem itself more widely, inviting any symmetry-practitioner — fabric designers, math-artists, chemists, interested people — to make these techniques their own. We truly believe, with plenty of reason, that this is the proper approach to understanding two-dimensional symmetrical patterns, at least their mathematical classification, and we’d like to see that perspective spread widely.

Who’s the book aimed at, and who would you love to read it?

The book is informal and open-hearted. We would love anyone who is interested in symmetry, from any direction, to engage with the book and learn how to use the Magic Theorem, and even dig into the orbifold theory behind it. We’ve aimed a lot of it at kids, frankly, and people that work with kids. There is a lot of stuff to try out and do!

We are making a long-term play. In fifty years’ time, in all humility and with no exaggeration, we hope that this has become the standard approach. We are getting there sidewise: this material is deep but it is also approachable, and we can spread the news through the broader mathematical community, like the readers of The Aperiodical.

What are some of your favourite things in the book?

This is a lot like asking which is a favourite child. First and foremost, though, we are passionate about the Magic Theorem itself, and the orbifold theory that fuels it! Conway’s colorful writing, the rich illustrations, and the many hands-on things to do are all satisfying. And we’re excited to be able to showcase the work of so many of our artist friends and associates.

How do the contributions from the different authors come together to make the book?

This book was shaped by the absence of its senior author. The text in The Magic Theorem is mostly from SoT, mostly written by John. Chaim prepared the new material and most of the revisions, and Heidi was instrumental in the initial layout and in the editorial process, ensuring the tone and level of the material is suitable for a broad reception.

How can people find out more and get hold of a copy?

Visit themagictheorem.com for information about the book, free hands-on activities, and more. The book is currently available for pre-order on the Routledge web site and will soon be “on the shelves” of major booksellers.