This is the final part in the Pascal pentalogy, a series of guest posts by David Benjamin exploring the secrets of Pascal’s Triangle.

Probability and combinations

In Part 1 of this series we stated that Pascal is credited with being the founder of probability theory – but credit also needs to be given to other mathematicians, in particular the Italian polymath Girolamo Cardano.

The connection between probability and the numbers in Pascal’s triangle can be shown by looking at the outcomes when one or more coins are tossed. The table below, from row two, lists the outcomes for one, two and three unbiased coins.

| |

| |||||||

| | |

| ||||||

| | | |

| |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

For four coins there is

Row four shows us that when three unbiased coins are tossed, the probability they will land showing two heads and one tail in any order is

As the sum of the

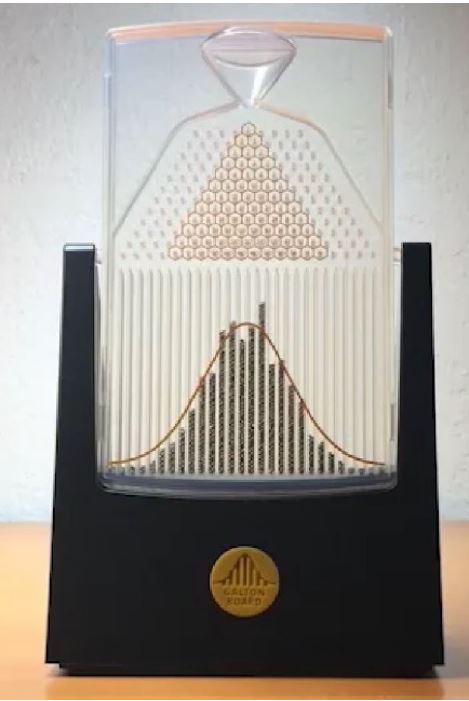

Quincunx

A Quincunx, or Galton Board, is named after the English explorer and anthropologist Francis Galton (1822-1911) – although this name is now less popular, because of Galton’s views on eugenics and racist attitudes.

The board is a triangular array of pegs. Balls are dropped onto the top peg and then bounce their way down to the bottom where they are collected in containers. Each time a ball hits one of the pegs, it bounces either left or right with an equal probability of

The Quincunx is like Pascal’s triangle with pegs instead of numbers. The number on each peg represents the number of different paths a ball can take to reach that peg. If there are

The probability of landing in the third bin from the right is

Statistics and permutations

The link between statistics and the triangle can be demonstrated using combinations. Consider these 5 mathematicians Euler, Pascal, Ramanujan, Hilbert and Conway and the possible teams for a three-legged race.

There are

EPR EPH EPC ERH ERC EHC PRH PRC PHC RHC

The formula to calculate the number of combinations is

In our example

| | | | | |

The animation film Of Dice and Men by John Weldon is a lovely way to introduce students to probability and statistics.

Pascal the polymath: mathematics, inventor, science and religion

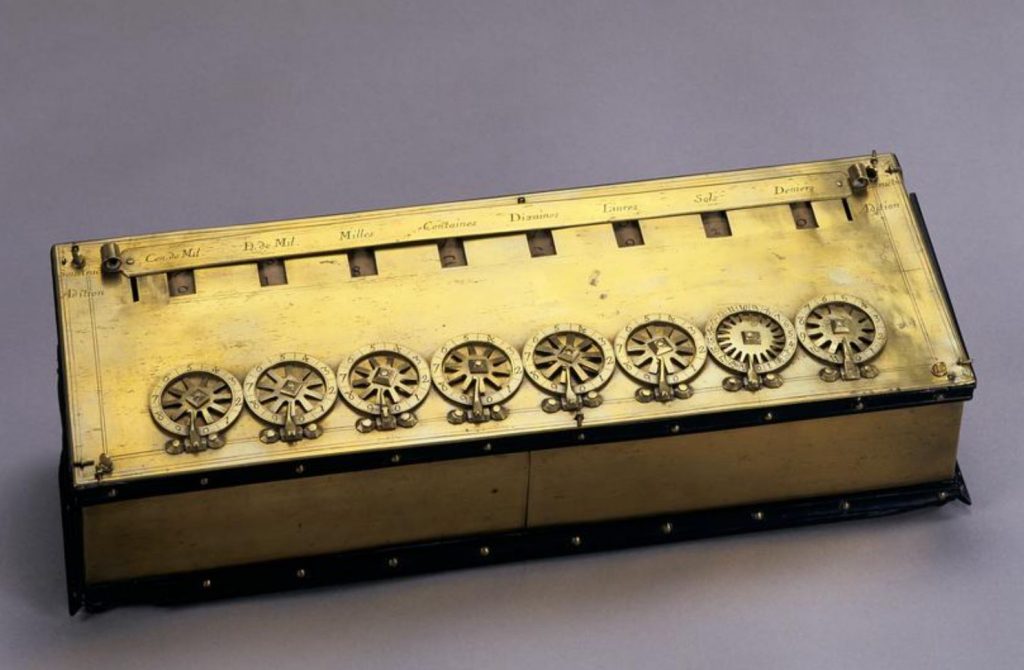

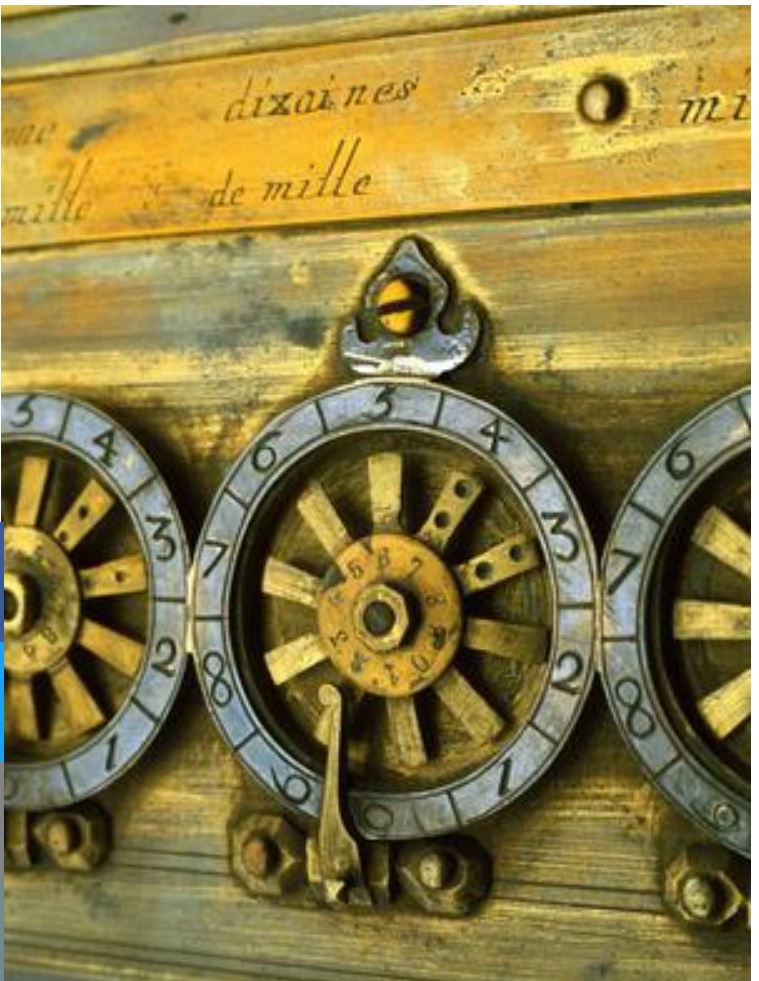

Pascal’s father was a tax collector and in 1642 Blaise invented a mechanical calculator to assist his father. It was called the Pascaline and had a wheel with eight movable parts for dialing. Each part corresponded to a particular digit in a number. Numbers could be added by turning the wheels located along the bottom of the machine. Subtraction was carried out by exploiting a method called nines’ complement representation, the use of which allows subtraction to be reduced to addition. Each digit in the answer was displayed in a separate window. The workings of the Pascaline are demonstrated here.

The Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris has one of the original Pascalines. The invention was not a commercial success – it was very expensive and often only purchased as a novelty rather than for use. Essentially, it was an adding machine. Subtraction was turned into a form of addition, as was multiplication. Division was done by repeated subtraction. Nines’ complement representation is still used in modern digital computers by a similar technique called ones’ complement which is used to represent negative numbers and hence perform subtraction in the same way as addition. Pascal did not discover this method but his calculator is the earliest known device to employ it. He continued to make improvements to his design until 1652.

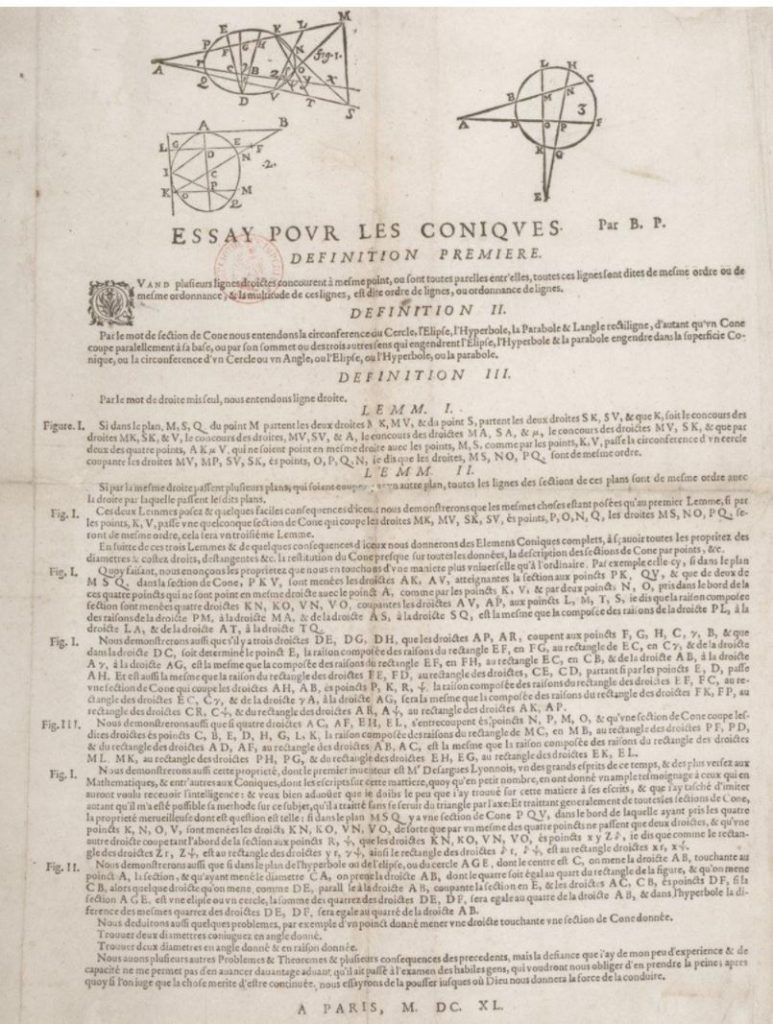

Conic sections – normally just called conics – are obtained when a mathematical cone is sliced by a plane. Depending on the angle of the slice, the intersections create a circle, an ellipse, a parabola and a hyperbola. Conics have many applications including the wheel of course, ophthalmic, parabolic mirrors and reflectors, telescopes, searchlights and projectile motion.

Pascal wrote a short treatise, Essai pour les coniques (Essay on Conics) when only 16. In it he included what is known as Pascal’s Theorem which states that if a hexagon is inscribed in a conic section then the three intersection points of opposite sides lie on a straight line – the Pascal line. The theorem [also referred to as Pascal’s Hexagrammum Mysticum Theorem] was his first important mathematical discovery and a breakthrough in the field of projective geometry.

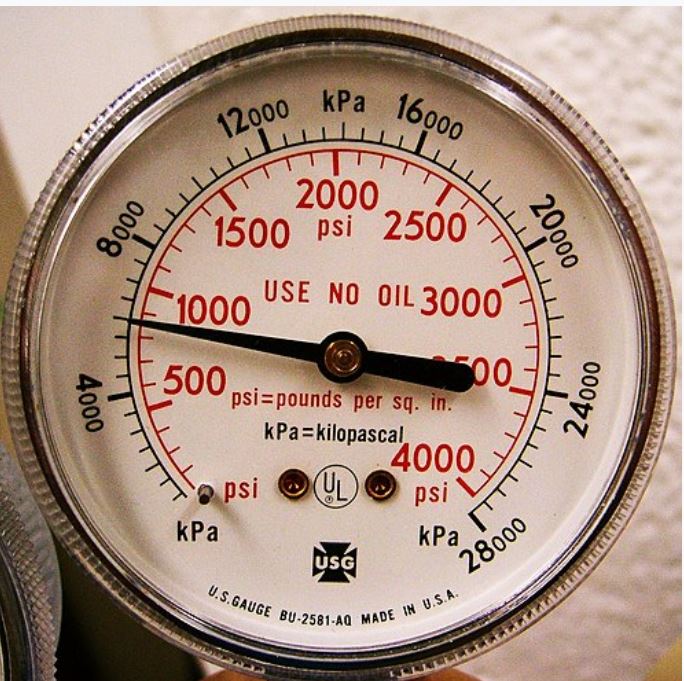

In 1647 Pascal expanded on the work of the Italian physicist Evangelista Torricelli, the inventor of the barometer by writing Experiences nouvelles touchant le vide (New experiments with the vacuum) in which Pascal gave detailed rules to describe to what degree various liquids could be supported by air pressure. In 1971 the SI unit for pressure [equal to one newton per square metre] was named the pascal.

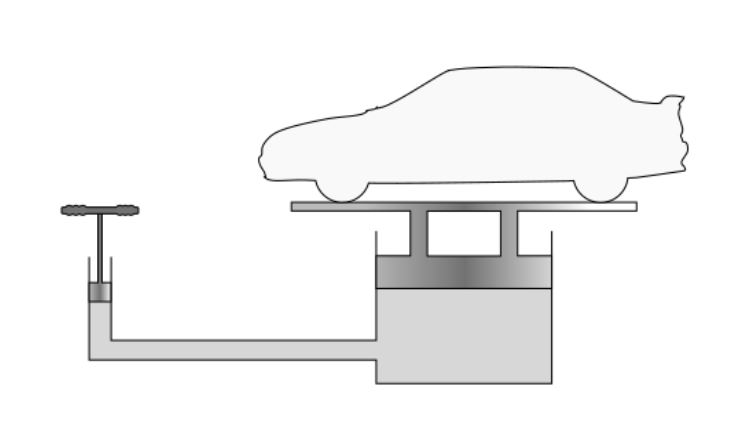

Also in 1647 he discovered Pascal’s Law of hydrostatics allowing for the development of the hydraulic press. Pascal himself used the principle to invent the syringe.

Pascal wrote an extremely influential theological work which was unfinished at the time of his death. It was posthumously called Pensées (Thoughts) and contained a detailed and coherent examination and defence of the Christian faith.

In 1655 Pascal was trying to invent a perpetual motion machine, a machine that continues to operate without drawing energy from an external source. The laws of physics now say this is impossible. Naturally he failed but he ended up inventing a basic roulette wheel, now upgraded and used in casinos as a game of chance.

The Swiss computer scientist Niklaus Emil Wirth, born in 1934, named one of his programming languages Pascal in honour of Blaise. Wirth along with Helmut Weber also designed the programming language named after another mathematician, Euler. [Recommended read: Euler: The Master of Us All ]

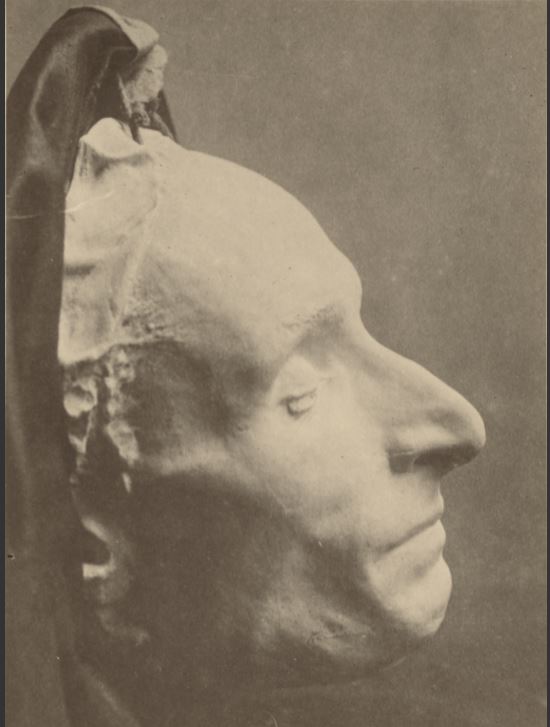

Pascal died in extreme pain at the young age of 39. He had a malignant growth in his stomach which had spread to his brain. Like many others, such as Évariste Galois and Franz Schubert, we are left wondering what else Pascal could have achieved had he lived longer. His work with Fermat into the calculus of probabilities helped the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz [1646-1716] develop the infinitesimal calculus. Pascal is buried in the Saint-Étienne-du-Mont church in Paris and his death mask is held at the J. Paul Getty museum in Los Angeles, California.

Great series!

Probability and statistics are both here shown to be connected to the triangle.

What an inventive engineer Pascal also was.