Welcome to the 241st Carnival of Mathematics, hosted here at the home of the Carnival, The Aperiodical. The Aperiodical is a shared blog written and curated by Katie Steckles (me), Christian Lawson-Perfect and Peter Rowlett, where we share interesting maths news and content, aimed at people who already know they like maths and would like to know more. The Carnival of Maths is administered by the Aperiodical, and if you’d like to host one on your own blog or see previous editions, you can visit the Carnival of Maths page.

You're reading: Columns

- You can donate to Matt’s kickstarter here, if you’re so inclined. At the time of writing, they’ve raised well over a quarter of a million pounds towards their £75k target, so I’m looking forward to them launching their own space mission before long.

- If you’re a teacher who wants to be involved, you can sign up here. Get the kiddos to estimate \( \pi \) by hand and they’ll get (I understand) a certificate, possibly their own value of lunar \( \pi \), and their name in a text file that goes to the moon. [Edited 2025-06-26 for formatting and to clarify that the personal \( \pi \) value is not guaranteed.]

Double Maths First Thing: Issue 2F

Double Maths First Thing says humf! and sort the big list

Hello! My name is Colin and I am a mathematician on a mission to spread the joy and delight in doing maths.

Not everyone takes delight in anagrams, but being clever, I do: delightfully, Sarina Wiegman is an anagram of “I win as manager”.

Links

Speaking of jumbling up letters, Tom Snelling has collated all of the books in the Library of Babel, a peculiar and slightly mathematical short story by Jorge Luis Borges.

In somewhat sad, but also “the dude was 97 and got to spend most of his life doing maths” news, Tom Lehrer died last week. He’s very much on the vision board of people I want to be like when I don’t grow up. Here is a lovely story about a reference in his work and I’ll note a degree of gladness that we didn’t all go together after all.

I’m looking forward to reading this, on convolutions, from Eli Bendersky.

Need some puzzles to while away the long summer? I know I do. For an hourly Countdown variant, follow the Hectoc bot, and for a daily “come up with a nice solution to a puzzle from AMS with a known answer” follow Suat Ayöz.

And here’s an article on knots in New Scientist that’s behind a paywall, which I linked to before realising it quotes my dear friend Nicholas Jackson. You definitely shouldn’t go to the archived version, that would be immoral.

Currently

If you’re in Edinburgh this weekend, Coburg House has an open house, where mathematical knitter Madeleine Shepherd will have work for sale.

Time is running out to submit an item to this month’s Carnival of maths and to this month’s TMiP animation challenge.

That’s all I’ve got for this week. If you have friends and/or colleagues who would enjoy Double Maths First Thing, do send them the link to sign up — they’ll be very welcome here.

If you’ve missed the previous issues of DMFT or — somehow — this one, you can find the archive courtesy of my dear friends at the Aperiodical.

Meanwhile, if there’s something I should know about, you can find me on Mathstodon as @icecolbeveridge, or at my personal website. You can also just reply to this email if there’s something you want to tell me.

Until next time,

C

Double Maths First Thing: Issue 2E

Double Maths First Thing might just let them watch a video

Hello! My name is Colin and I am a mathematician on a mission to spread the love and joy of struggling with a puzzle until it finally breaks up into beautiful bits.

This week, I’ve been looking at methods for how to board a plane. Turns out there’s a lot going on there. Monte Carlo methods, Lorentzian geometry, all sorts of tasty stuff.

Links

I’m not a wordsearch fan. I feel like there’s not much puzzle there. So I was surprised when Cracking the Cryptic suggested a wordsearch was an incredible puzzle, and amazed to find I agreed. (h/t to Tony Mann.)

On the to-read list for the summer holiday is this introduction to Galois fields — I particularly enjoyed (and felt) the grumble:

Many resources assumed either:

* It’s beyond your skill level so let’s oversimplify (“it’s hard, don’t worry about it”), or

* You had prior Pure Math studies in Abstract Algebra (“it’s easy, just use jargon jargon jargon”)

As much for the acronym as anything else, I’m pleased to link to the Database of Original and Non-theoretical Uses of Topology — topological data analysis is also on my list of things I’d like to learn one day.

I enjoyed @zenorogue’s discussion of different map projections.

Also in “problems I didn’t know I needed solved”, why are piano keys the widths they are?

There are many interesting papers from the Bridges conference in Eindhoven, last week, but I think my favourite is this one: Katherine Seaton’s exploration of hitomezashi stitching patterns on an isometric grids.

Currently

A big call-out from Dr Laura Taalman — an instant follow when I realised she was on Mathstodon — for a crochet art project you can join at Granny Life Crochet.

A reminder that you should join the Finite Group if you value off-beat mathematical discussions, and get your tickets for TMiP if you want to (a) learn more about talking maths in public and (b) come to the Pseudorandom Ensemble‘s show on the Wednesday evening.

That’s all I’ve got for this week. If you have friends and/or colleagues who would enjoy Double Maths First Thing, do send them the link to sign up — they’ll be very welcome here.

If you’ve missed the previous issues of DMFT or — somehow — this one, you can find the archive courtesy of my dear friends at the Aperiodical.

Meanwhile, if there’s something I should know about, you can find me on Mathstodon as @icecolbeveridge, or at my personal website. You can also just reply to this email if there’s something you want to tell me.

Until next time,

C

Double Maths First Thing: Issue 2D

Double Maths First Thing is halfway through Ouch to 5k.

Hello! My name is Colin and I am a mathematician on a mission to spread the joy of doing maths. And this week, I’ve been doing some cool maths, looking at Oskar van Deventer’s Blocks puzzle and models of crowd movement.

I’m also half-following the British & Irish Lions rugby tour: I’m told by reliable sources that no pair of the 47 squad members share a birthday. What are the chances?!

Links

Since pi approximation day is coming up next week, let’s start by looking at pi’s evil twin, the lemniscate constant.

KMB, via a comment on last week’s post pointed me at the fun-but-infuriating Intvania

Tom Mellor has sent me an equally infuriating set of mathematical dingbats. Enjoy/suffer!

Bob Bosch is doing, as usual, lovely things with knight’s tours.

And to round off a mathstodon-heavy link section (with more to come), here’s Fractal Kitty with some origami butterflies.

Currently

Not only is Tuesday Pi Approximation day, it’s also the traditional date for MathsJams around the world, including my corner of it; find your local Jam, or details on how to start one, here.

If you or someone you know has recently finished a great dissertation, and wants to write an article about it for Chalkdust (a magazine, I understand, for the mathematically curious), the IMA are offering a £100 prize to the best submission. Learn more here.

And if you’re interested in mathematical animation, the June TMiP Animation Challenge playlist is live. Read more about the challenge here.

That’s all I’ve got for this week. If you have friends and/or colleagues who would enjoy Double Maths First Thing, do send them the link to sign up — they’ll be very welcome here.

If you’ve missed the previous issues of DMFT or — somehow — this one, you can find the archive courtesy of my dear friends at the Aperiodical.

Meanwhile, if there’s something I should know about, you can find me on Mathstodon as @icecolbeveridge, or at my personal website. You can also just reply to this email if there’s something you want to tell me.

Until next time,

C

Double Maths First Thing: Issue 2C

Double Maths First Thing couldn’t possibly comment.

Hello! My name is Colin and I am a mathematician on a mission to spread joy and delight in engaging with maths, for any reason or for none. I’ve made it back from rehearsal and am feeling a lot better (thanks for asking).

(By the way, if you know of any Colin-shaped work, please let me know about it — I’d love something stable, remote, part-time and reasonably paid but neither soul-crushing nor burnout-inducing. Plus the moon on a stick, obviously. I can write. I can code. I can solve weird problems. There must be something, right?)

Links

Let’s start with something on my to-read list: Tai-Danae Bradley’s guide to category theory and notes on Applied category theory. I feel like there’s something going on a level up from where I normally look at things and that category theory might be a lens to examine it through.

A nice series of posts by Ioanna Georgiou and Asuka Young on mathematical themes implicit in the situation-comedy Friends, which I gather many cooler people than me are into.

We all know and love the rhombic dodecahedron, but Robin Houston is at pains to point out that it’s not the RD, but a RD..

David Eppstein has been to Kanazawa, Japan and found plenty of geometrical street art. Meanwhile, John Carlos Baez is in Athens, where the maths department is full of graffiti.

And following on from Minesweeper in issue 2B, we’ve now got Mark Round’s Primesweeper. Which is not in the slightest bit stressful.

Currently

I enjoyed the Finite Group livestream last week, especially the bit about bees’ ancestry following a Fibonacci sequence. You can join and, for a very reasonable monthly outlay, have access to some of the previous livestreams and all of the new ones. (You can even join for free and hang out in the Discord with awesome maths people.)

One small appeal from me: it’s striking, looking back through past DMFTs how heavily the links skew towards male (or male-presenting) mathematicians. I’m keen to amplify the voices of women and other members of under-represented groups. if you stumble on a link spoken in such a voice and think “I’m not sure Colin would be interested” or “I don’t want to bother him” — I’ll tell you right now, it’s no bother and I’m certainly interested.

That’s all I’ve got for this week. If you have friends and/or colleagues who would enjoy Double Maths First Thing, do send them the link to sign up — they’ll be very welcome here.

If you’ve missed the previous issues of DMFT or — somehow — this one, you can find the archive courtesy of my dear friends at the Aperiodical.

Meanwhile, if there’s something I should know about, you can find me on Mathstodon as @icecolbeveridge, or at my personal website. You can also just reply to this email if there’s something you want to tell me.

Until next time,

C

Double Maths First Thing: Issue 2B

Double Maths First Thing could really do with a hot lemon and honey

Hello! My name is Colin and I am a mathematician on a mission to shift this blooming cold before the weekend, when I’m meant to be in Peterborough to rehearse for the PRE show in August. Have I mentioned that previously? We’re playing at the Warwick Arts Centre as part of Talking Maths in Public.

Speaking of TMiP (and I know this belongs under “Currently”, but continuity > consistency), the animation challenge for July is live. Can you show that two reflections make a rotation?

As I say, I’m a bit under the weather this week (which might explain, if not excuse, my triple DNF at the cubing competition; I’ll be trying again in September. One of them was very close, but you don’t get anything for that) and I’ll be keeping DMFT correspondingly short.

Links

A lovely/horrifying thing to start with this week: James Haydon attempts to treat the UK passport application service like a game and hack his way to success.

The only horrifying thing about Simon Tatham’s Portable Puzzles Collection is the amount of time it has sucked out of the world over the last however-many years. His version of Minesweeper — which, unlike the version that comes with a popular OS, is always solvable, is twenty years old.

I’m a great fan of mediocre football. I grew up somewhere without a serious football team (Scotland), so I appreciate the benefits of being a bit rubbish. Had Alan Turing been better at chess, computers might not have become so.

Another great name of British espionage and subterfuge was William Playfair, who — among other pieces of villainy, invented (or at least popularised) the pie chart.

Meanwhile, there’s been some commotion over the recently-constructed monostable tetrahedron, a shape that always lands on the same face. The paper claims that they built and lost a model in the 1980s. It’s not lost, it’s on Colin Wright’s desk, potato patato.

Last up, here’s a guide to factoring from Orman and Schroeppel.

Currently

The deadline for the next Carnival is… not approaching as quickly as I thought, it’s a double-header and posts need to be in by August 1st.

What is approaching quickly is the next Finite Group livestream: all four of the generators will be trying to tell us something we don’t know on Friday July 4th (7pm UK time). Free membership grants you access to the Discord, where all the cool people hang out, and paid memberships allow you to watch the livestreams, as well as other goodies.

That’s all I’ve got for this week. If you have friends and/or colleagues who would enjoy Double Maths First Thing, do send them the link to sign up — they’ll be very welcome here.

If you’ve missed the previous issues of DMFT or — somehow — this one, you can find the archive courtesy of my dear friends at the Aperiodical.

Meanwhile, if there’s something I should know about, you can find me on Mathstodon as @icecolbeveridge, or at my personal website. You can also just reply to this email if there’s something you want to tell me.

Until next time,

C

When the moon hits your eye with a big piece of \( \pi \)…

We do these things, not because they are difficult, but because they are ridiculous

– Matt Parker, probably

Matt Parker is going to the moon. I mean, not literally. Everyone’s favourite Stand-Up Mathematician is the sort of person who’s more likely to go to hyperspace than to space. However, when Matt was approached to do “something ridiculous” with spare computing power on a lunar rover, there was only ever going to be one outcome: an attempt to calculate \( \pi \) on the moon.

But… why?

That is an excellent question, beautifully presented. I compliment you for asking it. Next!

Moon-te Carlo

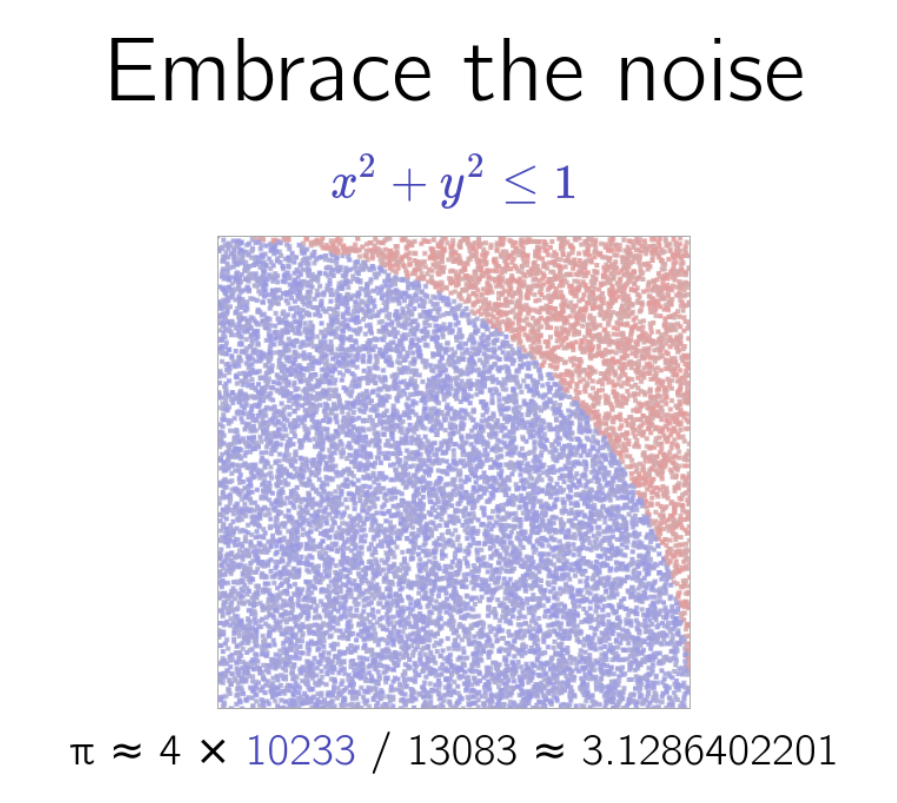

Because it’s important to do ridiculous things properly — there’s no point in going to the moon and doing calculations you could do on Earth — Matt made the decision to approximate \( \pi \) using the readings from the rover as a source of randomness for a Monte Carlo calculation.

Monte Carlo methods are typically used to work things out when it’s too difficult or too boring to do them analytically. While there were some earlier randomised calculation methods — Buffon’s needle, for example — the first real Monte Carlo experiment was done by Stanisław Ulam while recovering from an illness. Ulam wondered how likely it was that a game of solitaire would come out successfully and, rather than calculate it properly, decided to play a hundred games and count how many they won. It was a short step from there to the atomic bomb.

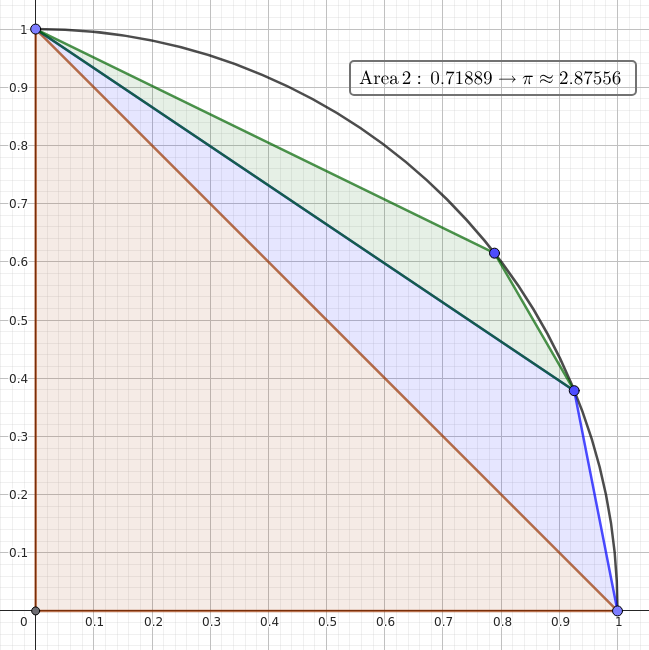

Matt showed the standard Monte Carlo approach to calculating \( \pi \) in the video announcing the moon \( \pi \) project — it’s often used as a simple example when introducing the idea. If you put a circular dartboard in a square box that just fits it, and threw darts at the box, assuming you were equally likely to hit any point in the box, each dart would have a probability of \( \frac{\pi}{4} \) of hitting the dartboard. If you threw 100 darts and 80 of them hit the board, you would conclude that \( \frac{\pi}{4} \approx 0.8 \) and that \( \pi \approx 3.2 \). Throwing more darts should get you a better estimate — although rather slowly. If you throw \( N \) darts, the standard error of your probability is proportional to \( N^{-\frac{1}{2}} \), which means becoming half as inaccurate requires four times as many darts.

Holding out for a Hero

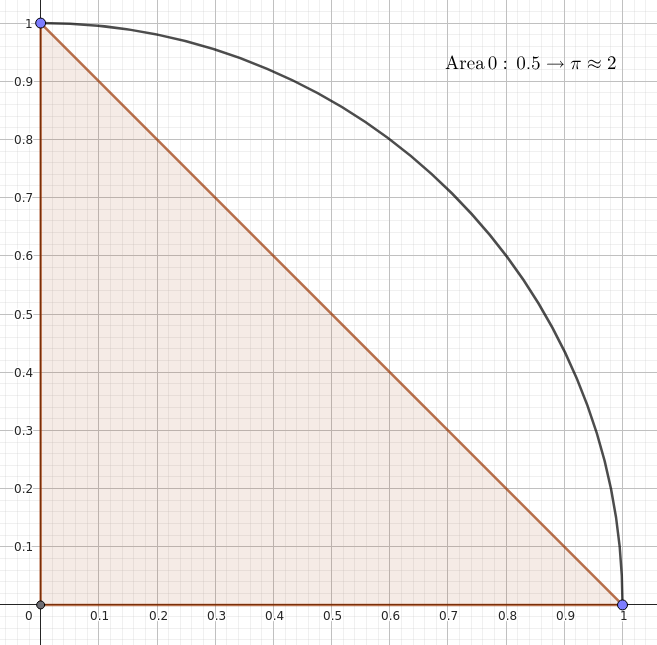

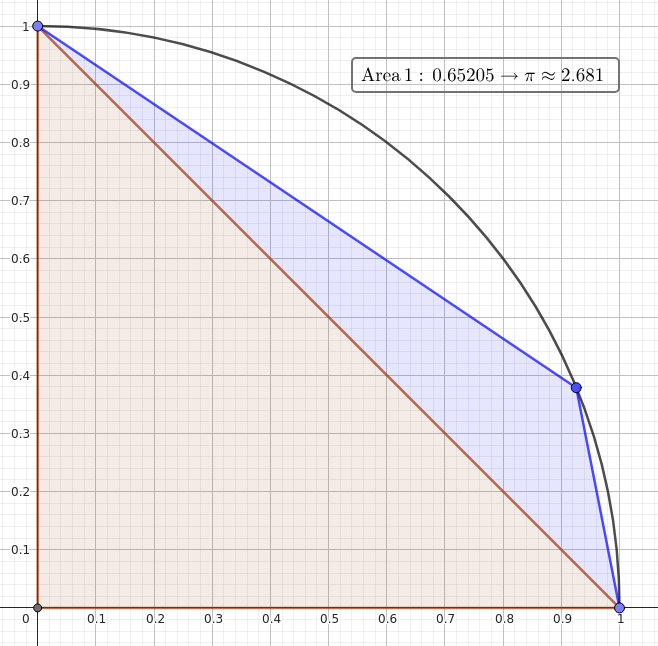

Matt famously thinks Heron’s formula is one of trigonometry’s most remarkable results. It’s been known to make Matt extremely emotional. So, naturally, my first thought was “I bet an approach based on Heron’s formula could converge more quickly.”

And it could! The approach entailed starting with a right-angled triangle with legs of length one inside a unit circle in the first quadrant. It would then pick a random x-coordinate between 0 and 1, figure out the corresponding point on the arc, and add a triangle based on the two adjacent points. Here’s the code. It converges to several decimal places within 10,000 iterations.

But that’s not really Monte Carlo, now, is it?

That is an excellent question, beautifully presented. I complime… what do you mean, I need to answer it? Who’s writing… OK. Fine. Sheesh.

You’re right, this isn’t a traditional Monte Carlo method. While it uses random points, it doesn’t use them to generate a probability. I do still maintain that it’s technically a Monte Carlo method, using a very involved adaptive weighting function, but I take the point.

What about proper Monte Carlo methods?

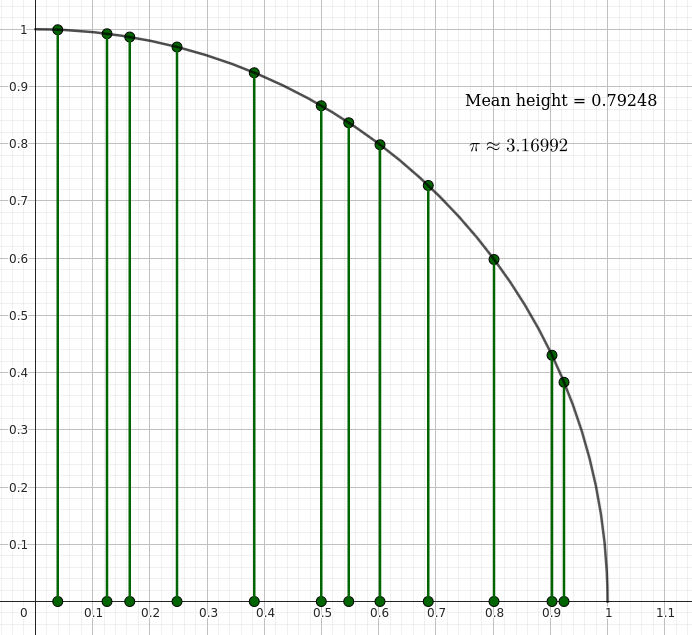

A less sophisticated (but still significantly more efficient than the integration-by-darts method) approach is to use the fact that \( x^2 + y^2 = 1 \) on the unit circle. If you pick an \( x \) value at random, you can immediately calculate the probability of a random \( y \) value giving a point inside the circle — it’s \( \sqrt{1- x^2} \). Rather than sample and add 1 or 0 to your total to approximate the probability, why not just add the probability? This converges very nicely.

I’m not officially allowed to reveal that the reason for my interest in calculating \( \pi \) on the moon is that I’m helping to design Matt’s experiment, or that my codename is FizzBuzz Aldrin. (Is that lede sufficiently buried? Excellent.) And I’m definitely not officially allowed to say what we’re actually doing, because I imagine Matt will want to do a video about it.

However, I can say that the method above is equivalent to the fact that the expected distance between a point on the unit circle and an axis — any axis — is \( \frac{\pi}{4} \). By extension, using the magical incantation “SYMMETRY!” and a magisterial wave of the hand, it turns out that any point on a unit sphere is — on average — \( \frac{\pi}{4} \) from any axis of the sphere. That’s a fact that could be exploited, just to pick a random example, by a simulated rover making random moves on the surface in a sort of random moonwalk.

It would take small steps for a rover, and giant LOOPs for Matt-kind.