Google Books Ngram Viewer is a Google labs product for comparing terms in books between 1500 and 2008. The idea seems to be to track trends in language. An interesting idea.

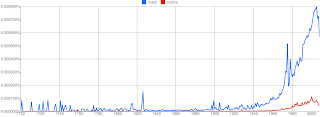

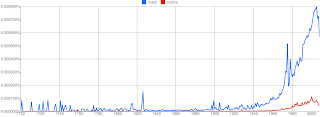

Anyway, both Christian Perfect (@christianp) and Daniel Demski (@dranorter) sent me the Ngram comparing “math” with “maths”. Christian observed: “bad news: it looks like ‘math’ outdid ‘maths’ for a lot of history”. Daniel observed: “Apparently the term maths is pretty recent? “.

Here is the graph for math and maths from 1700-2008 (click to enlarge).

So from these data it seems math has been much used through history, earlier and to a greater extent than maths. I have no preconceptions about which came first; what seemed surprising to me was how early either was used.

The Google Books Ngram Viewer info page seems to claim that “British English” is a subset of “English” limited to books published in Britain, but if you look at the “British English” version of the graph from 1600-1700 there’s some activity for “math” that doesn’t occur using the English corpus. Latin was used as the language for writing science into the 1700s, so it seems unlikely people would be publishing works with “math”, “maths” or “mathematics” during this period.

Use of “math” and “maths”

Anyway, let’s look at some of the use of “math” and “maths”.

In abbreviations

You do see both “math” and “maths” used as abbreviations of mathematics, or at least for “mathematica”, in university course catalogues (e.g. Annual Report of the President of Harvard College, 1863 and The Oxford Ten-Year Book, 1863). I’m discounting these though, because you see a lot of terms abbreviated in such catalogues that aren’t used as words on their own. In these documents you see “Hist.” for history, “Rhet.” for rhetoric, “Eng.” for english and many more, yet you don’t hear people referring to history as “hist”.

A similar example you still see today is in the abbreviation of journal titles. For example, you see “Proc. Lond. Math. Soc.” for “Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society”, just like you see “Proc. Roy. Soc.” for “Proceedings of the Royal Society”. Since we don’t commonly see “Lond” used for London, I am discounting this use of “math” for mathematics.

Other words

Sometimes the use of math simply refers to another word, brought into the search due to lack of semantic meaning. For example:

Incorrecly coded data

Some books are marked with the incorrect date, for example: “ICT for Primary Maths” by Jill Clare (1904) (actually early 2000s) and Business week issues 2652-2660 – 1934 (actually 1980)

Otherwise, some words are just incorrectly OCR‘d, e.g. “Mach.” in Macbeth or “wrath” in “An Exposition with Practicall Observations Continued Upon The Eighteenth, Nineteen, Twentieth, and twenty-one Chapters of the Book of Job” by Joseph Caryl (1658).

Etymology

The Online Etymology Dictionary says:

math: Amer.Eng. shortening of mathematics, 1890; the British preference, maths, is attested from 1911.

I haven’t been able to find these cases, but it’s true that around the early 20th Century the use of “math” and “maths” moves out of the sorts of abbreviation-in-a-list-of-abbreviations cases above and what I would consider to be use of these terms in normal sentences to mean “mathematics” starts to be seen in the results.

For “math”, there are some interesting titles but without online previews of the whole book, such as ‘Patented blocks for teaching math with geometric forms’ (1925). Boys’ Life, November 1926 (pp. 14-15) carries a story in which there is a certain amount of concern over who will pass their math exam, and an advert in Popular Mechanics magazine, June 1944 (p. 51) suggests math is in common use, offering the chance, using a slide rule, to “Become a MATH Wizard!” and solve “the toughest math problems in a flash!”.

On the “maths” front, we have references to “swatting up” on “these beastly maths” in These Lynnekers by J.D. Beresford in 1916 (p. 43) and the far more appealing “Aren’t maths beautiful? Is there anything more beautiful than a sphere?…” in The Strangers’ Wedding: The Comedy of a Romantic by W. L. George in the same year (p. 23).