Earlier this week my sister-in-law (“SIL” from now on) sent me an email asking for help. She’s a dance teacher, and her class need to rehearse their group pieces before their exam. She’d been trying to work out how to timetable the groups’ rehearsals, and couldn’t make it all fit together. So of course, she asked her friendly neighbourhood mathmo for help.

My initial reply was cheery and optimistic. It’s always good to let people think you know what you’re doing: much like one of Evel Knievel’s stunts, it makes you look even better on the occasions you succeed.

I’d half-remembered Katie’s friend’s Dad’s golf tournament problem and made a guess about the root of the difficulty she was having, but on closer inspection it wasn’t quite the same. I’m going to try to recount the process of coming up with an answer as it happened, with wrong turns and half-baked ideas included.

Here’s a summary of what she told me:

- There are 7 groups, each with a leader (who must be in charge of the choreography or something)

- There are five timetable periods available, each an hour long.

- Each dancer should get at least 3 hours’ rehearsal time.

- Some students belong to more than one group.

She also gave me the list of dancers in each group. (Names have been changed to make the maths easier)

I could’ve pretended these are their real names, but then this post would have to be about the astronomically unlikely coincidence of being presented with a real-world maths problem with such helpfully ready-made notation.

| 1: Amelia | Bmelia | Cmelia | Dmelia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2: Emelia | Dmelia | Fmelia | Gmelia | |

| 3: Hmelia | Cmelia | Imelia | Jmelia | Kmelia |

| 4: Lmelia | Mmelia | Nmelia | Omelia | |

| 5: Pmelia | Gmelia | Qmelia | Rmelia | |

| 6: Smelia | Rmelia | Tmelia | Umelia | |

| 7: Vmelia | Smelia | Pmelia | Tmelia | Jmelia |

SIL was concerned that among the people in two groups were the leaders of two other groups – Smelia and Pmelia. I wasn’t sure that this made any difference, but it was an extra bit of information to bear in mind in case it later led to a complication I hadn’t thought of.

My first instinct was that I needed to come up with an individual timetable each dancer. SIL’s original email wasn’t very clear about what exactly she needed, so I thought that giving each dancer 3 hours would turn out to be difficult – maybe the room can only accommodate so many people at once, for example. With that in mind, I set about looking for ways to assign dancers to periods while maximising the length of time groups had together.

First: if every dancer gets exactly 3 hours’ rehearsal, is it possible to look at every permutation of timetables and rank them by how well they fit the constraints? In other words, can I brute force it?

There are 20 dancers, each of whom need to be timetabled in 3 of 5 periods, so 12 dancers in each period. That’s ${20 \choose 12} = 125970$ choices of dancers for each period, and a total of

\[125970^5 = 31720180268697990275700000 \]

timetables for the whole class. Most of those will be invalid, giving some dancers more or less rehearsal time than they need, but any number wider than your field of vision is a bad candidate for brute forcing.

Alternately, each dancer is assigned 3 out of 5 periods, and that happens for each of the 20 dancers. Looking at it this way, there are

\[ {5 \choose 3}^{20} = 10^{20} = 100000000000000000000 \]

timetables to consider. While that’s a million times smaller than my first guess and the least significant digit is starting to hove into my peripheral vision, that’s still far too big. so I think brute forcing is out, and I’ll have to do some thinking.

I’m not very good at thinking.

Strategy 2: get someone else to do it, preferably a computer.

This is some kind of linear programming problem, so I did a quick google and ended up at GLPK: the GNU Linear Programming Kit. I’d never heard of it before, but further googling led to this program to solve the knapsack problem on wikibooks.org which looked enticingly gnomic:

# en.wikipedia.org offers the following definition:

# The knapsack problem or rucksack problem is a problem in combinatorial optimization:

# Given a set of items, each with a weight and a value, determine the number of each

# item to include in a collection so that the total weight is less than a given limit

# and the total value is as large as possible.

#

# This file shows how to model a knapsack problem in GMPL.

# Size of knapsack

param c;

# Items: index, size, profit

set I, dimen 3;

# Indices

set J := setof{(i,s,p) in I} i;

# Assignment

var a{J}, binary;

maximize obj :

sum{(i,s,p) in I} p*a[i];

s.t. size :

sum{(i,s,p) in I} s*a[i] <= c;

solve;

printf "The knapsack contains:\n";

printf {(i,s,p) in I: a[i] == 1} " %i", i;

printf "\n";

data;

# Size of the knapsack

param c := 100;

# Items: index, size, profit

set I :=

1 10 10

2 10 10

3 15 15

4 20 20

5 20 20

6 24 24

7 24 24

8 50 50;

end;

Unfortunately, the documentation for GMPL, the language used by GLPK, is hard both to find and to read.

For reference, here’s the GMPL language reference. It’s a breezy 70 pages, but my eyes go fuzzy when I look at it.

While I could probably get it to find a solution for me, I’d probably spend longer learning how to write the program than I would have spent coming up with the answer on my own. So, I made a mental note to learn all about GMPL at a later date, because it does look rather marvellous, and decided to phone SIL and fish for more hints.

On talking to SIL, it turned out I was solving the wrong problem! I’d assumed there’d be a constraint on the number of dancers who could rehearse at once, and that dancers wouldn’t want to be assigned more than 3 periods, so the problem would be putting the right people in the room at the same time. That wasn’t the problem at all: everybody can rehearse at the same time, and SIL was perfectly happy to work her charges like dogs for the full 5 periods if required. The real problem was how to make sure that each group leader got at least 2 hours with their whole group. So even if everybody’s in the room for all 5 sessions, the timetable should tell them which group’s dance they should be rehearsing at any time.

Suddenly, the problem looked a lot more manageable: for the sake of simplicity, I can begin by assuming everyone’s in the room, and I just need to assign periods to groups, making sure not to timetable two groups sharing a dancer in the same period.

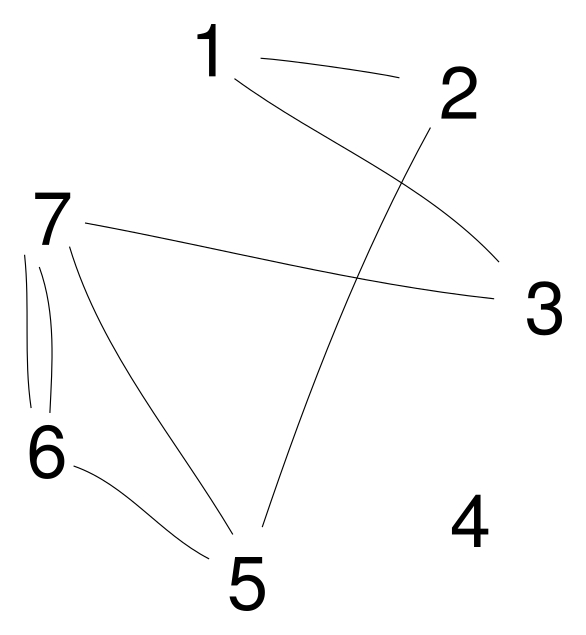

I immediately returned to a little doodle I’d made while thinking about how to avoid thinking earlier.

There’s a line between two groups if they share a dancer. Groups 6 and 7 share two dancers.

While some dancers belong to two groups, no dancer belongs to three groups. That’s good: if a dancer belongs to three groups, then it’s impossible to give all three of those groups two hours rehearsing with all their members, since there are only 5 hours available.

Next I thought about the timetable from the perspective of a dancer who belongs to two groups: for two hours they’ll be with one group, for two different hours they’ll be with the other, and there’s another hour spare. If I can split the groups into two sets so that none of the groups in each set have a dancer in common, I’m done: I can timetable the groups in the first set to dance together for the first two hours, and then the groups in the second set will dance together in the two following hours.

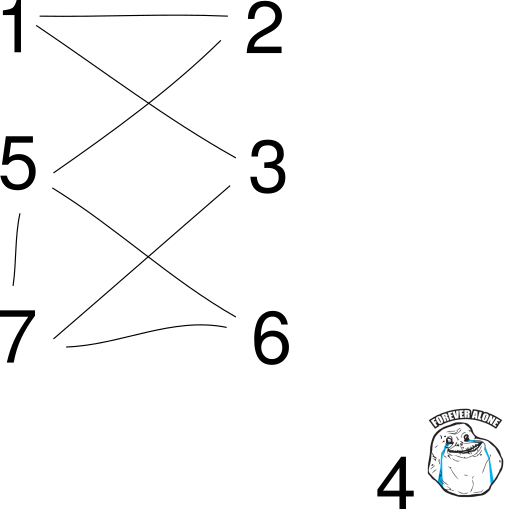

So I needed the graph I’d drawn above to be bipartite. Unfortunately, it isn’t:

No matter how I shuffle things about, that triangle involving groups 5,6 and 7 will scupper any attempt to draw a bipartite graph. It also became clear at this point that group 4 is either really unpopular or really snooty.

So, it was impossible. But at least now I know it’s impossible! I rang SIL to tell her the good news: she hadn’t wasted hours stupidly, it really isn’t possible to timetable her groups fairly. SIL’s sister (aka my wife) told me not to bother her with the details, but I felt that my findings were only good news if I explained my reasoning. At least I didn’t use the word ‘bipartite’. To offer extra comfort, I worked out that the only spanner in the works was Pmelia: she belongs to groups 5 and 7, and only removing her edge from the graph would make it bipartite.

I asked if it would be possible to swap Pmelia out of group 7 for one of the members of group 4, maybe Nmelia. Unfortunately, SIL said that wasn’t possible. So, having realised that Pmelia was the problem (should’ve guessed: alliteration is a powerful epistemological tool), I came up with a “least-bad” timetable:

- In the first two periods, groups 2, 3 and 6 should rehearse with all of their dancers.

- In the following two periods, groups 1, 5 and 7 should rehearse with all of their dancers, but 7 will have to make do without Pmelia.

- In the fifth period, group 7 should rehearse for another hour, with Pmelia included this time.

- Group 4 can do whatever the heck they like.

Now, having had all this marvellous insight, there was still the chance that my timetable would be unacceptable for some reason SIL hadn’t yet mentioned, but I got lucky and she was very happy with it. She did ask what the dancers should do when they’re not timetabled. Rather than get bogged down in more unwelcome thinking, and since SIL didn’t have any particular aims for them, I told her to get them to sort themselves out: there’s no point making up a rule unless you really need to.

So, that’s the story of how I accidentally got my graph theory wedged in my sister-in-law’s dance class. I quite like the simplicity of my final answer, though I expect I’ll carry a grudge against people called Pmelia for a long while.