Boris Konev and Alexei Lisitsa of the University of Liverpool have been looking at sequences of $+1$s and $-1$s, and have shown using an SAT-solver-based proof that every sequence of $1161$ or more elements has a subsequence which sums to at least $2$. This extends the existing long-known result that every such sequence of $12$ or more elements has a subsequence which sums to at least $1$, and constitutes a proof of Erdős’s discrepancy problem for $C \leq 2$.

You're reading: Columns

Manchester MathsJam Writeup, February 2014

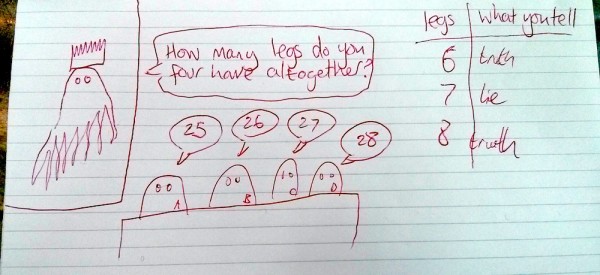

We started the evening with a logic puzzle Paul had found on Stack Exchange, which is detailed in the diagram we drew:

Ghostcube by Erik Åberg

[youtube url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85LJh4sFi_M]

Erik Åberg is selling a short documentary about these lovely foldy cubes on his website.

via Will Davies on Twitter

Babbage’s difference engine is really, really pretty

Hands up if you knew there was a working replica of Babbage’s difference engine in California.

(My hand is not up.)

This glorious machine lives in the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. A company called xRez Studio, which specialises in taking extremely high resolution gigapixel photos of things, has taken some extremely high resolution gigapixel photos of the difference engine. They’re so lovely that it feels wrong to be looking at them at work.

The photos are only avaiable on xRez Studio’s website, or as part of the Babbage exhibit at the Computer History Museum, but xRez has also released a video of the machine in action, which we can embed here.

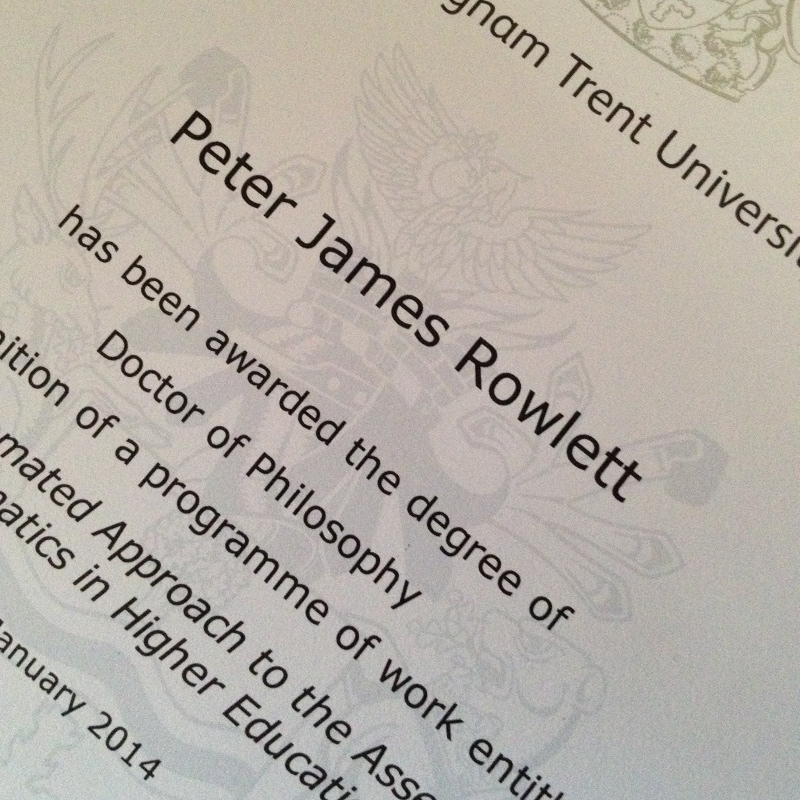

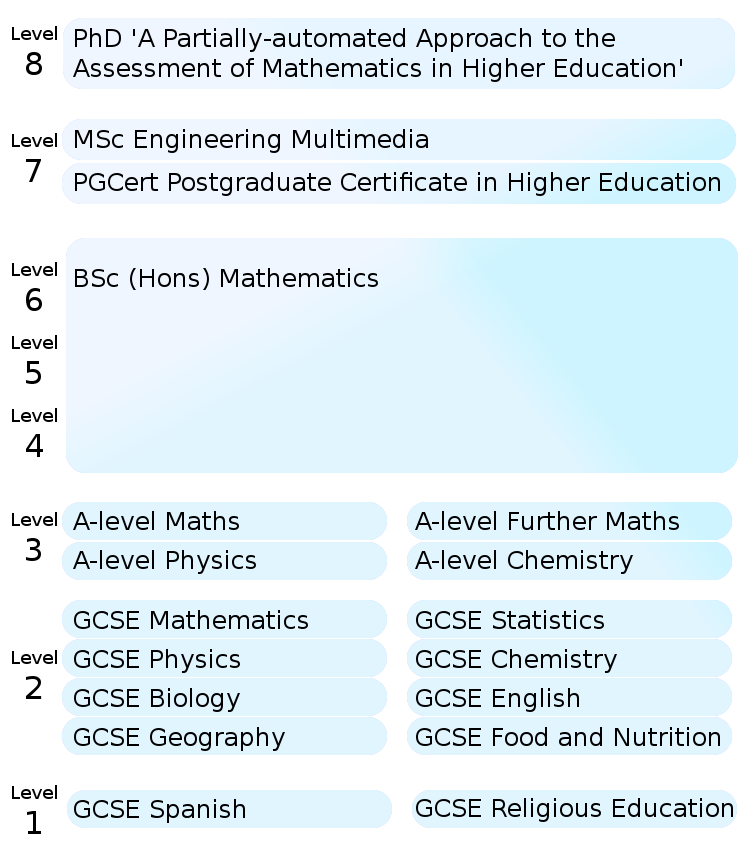

You have completed level 8. Game over. Insert coin.

(See QCF.)

(See QCF.)

That is to say, the university have sent me a degree certificate, and I’ve shown it to the bank. So that’s pretty darn official.

The neuroscience of mathematical beauty, or, Equation beauty contest!

Neuroscientists Semir Zeki and John Paul Romaya have put mathematicians in an MRI scanner and shown them equations, in an attempt to discover whether mathematical beauty is comparable to the experience derived from great art.

They’ve detailed the results in a paper titled “The experience of mathematical beauty and its neural correlates”. Here’s a bit of the abstract:

We used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to image the activity in the brains of 15 mathematicians when they viewed mathematical formulae which they had individually rated as beautiful, indifferent or ugly. Results showed that the experience of mathematical beauty correlates parametrically with activity in the same part of the emotional brain, namely field A1 of the medial orbito-frontal cortex (mOFC), as the experience of beauty derived from other sources.

BBC News puts it: “the same emotional brain centres used to appreciate art were being activated by ‘beautiful’ maths”. This is interesting, according to the authors, because it investigates the emotional response to beauty derived from “a highly intellectual and abstract source”.

As well as the open access paper, the journal website contains a sheet of the sixty mathematical formulae used in the study. Participants were asked to rate each formula on a scale of “-5 (ugly) to +5 (beautiful)”, and then two weeks later to rate each again as simply ‘ugly’, ‘neutral’ or ‘beautiful’ while in a scanner. The results of these ratings are available in an Excel data sheet.

This free access to research data means we can add to the sum total of human knowledge, namely by presenting a roundup of the most beautiful and most ugly equations!

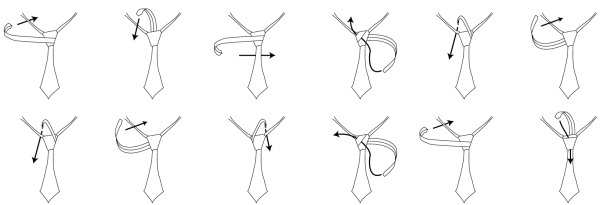

Tie, tie, tie a tie / Fly, fly, fly as you might

Novel knot news now! You might already be aware that there are 85 ways to tie a tie. Well, cast that preconception aside because there are actually loads.