A conversation about mathematics inspired by a taxicab. Presented by Katie Steckles and Peter Rowlett.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS | List of episodes

A conversation about mathematics inspired by a taxicab. Presented by Katie Steckles and Peter Rowlett.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS | List of episodes

There seem to be a lot of numerical coincidences bouncing around concerning the new year 2025. For example, it’s a square number: \( 2025 = 45^2 \). The last square year was \(44^2 = 1936\), and the next will be \(46^2=2116\).

The other one you have likely seen somewhere is this little gem: that 2025 equals both \((1+2+3+4+5+6+7+8+9)^2\) and \(1^3+2^3+3^3+4^3+5^3+6^3+7^3+8^3+9^3\).

But there are more – after all, 2025 does appear in over a thousand search results at the OEIS. Here’s a little collection:

Over at the Finite Group, members (including me and Katie) have been discussing what in maths news has excited us this year. Here’s a summary.

Brayden Casella and fellow authors claimed that there exists a non-terminating game of Beggar-My-Neighbour, solving one of John H. Conway’s anti-Hilbert problems. Beggar-My-Neighbour is a card game similar to War in which two players deal cards onto a shared pile, aiming to win all the cards into their hand. Matthew Scroggs made a bot: Beggar-my-neighbour forever. In other game theory news, Othello is solved.

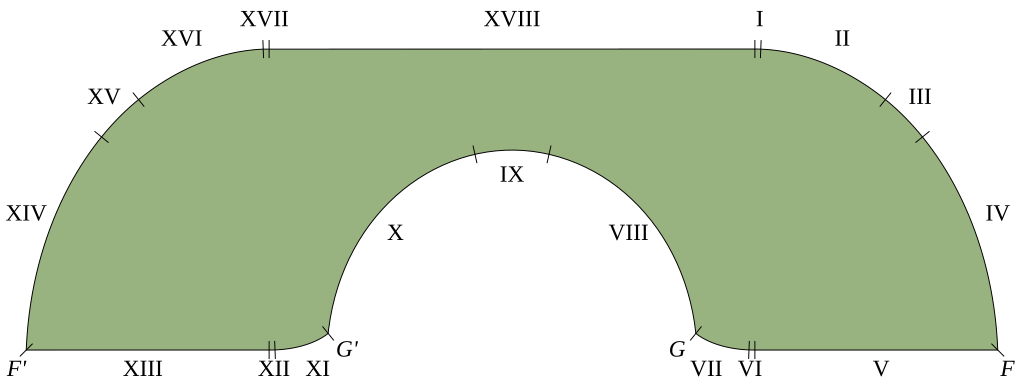

Jineon Baek claims a resolution to the moving sofa problem. This considers a 2D version of turning a sofa around an L-shaped corner, attempting to find a shape of largest area. (There are some nice animations at Wolfram MathWorld.) Baek offers a proof that the shape above, created by Joseph L. Gerver in 1992, is optimal.

The Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search (GIMPS) announced a new Mersenne prime: \(2^{136,279,841}-1\). You can get maximum excitement about this news from Ayliean on TikTok, and join in the fun by signing up to record yourself saying a chunk of the prime for the Say The Prime project.

One thing that’s new, apart from the prime itself, is that the work was done on a network of GPUs, ending “the 28-year reign of ordinary personal computers finding these huge prime numbers”. Also this was the first GIMPS prime discovered using a probable prime test, so the project chose to use the date the prime was verified by the Lucas-Lehmer primality test as the discovery date. In other computation news, the fifth Busy Beaver number has been found, as well as 202 trillion digits of pi.

A new elliptic curve was discovered, breaking a record set in 2006 and pushing at the limits of current methods for finding them. Here’s some background on the curves and some of the characters involved.

This year also saw a proof of the geometric Langlands conjecture, and this article explains why this is such a big deal.

We’re all still excited about the discovery of the aperiodic monotiles, and the result passed peer review and was published this year.

And finally, it may not be top research news, but 2024 was also the year that Colin Beveridge started his Double Maths First Thing newsletter. Subscribe to the newsletter here, and check out the archive of past issues here at The Aperiodical.

Finite Group is a friendly online mathematical discussion group which is free to join, and members can also pay to access monthly livestreams (next one Friday 20th December 2024 at 8pm GMT and recorded for viewing later). The content isn’t at the level of the research mathematics in this post, but we try to have a fun time chatting about interesting maths. Join us!

In the last Finite Group livestream, Katie told us about emirps. If a number p is prime, and reversing its digits is also prime, the reversal is an emirp (‘prime’ backwards, geddit?).

For example, 13, 3541 and 9999713 are prime. Reversing their digits we get the primes 31, 1453 and 3179999, so these are all emirps. It doesn’t work for all primes – for example, 19 is prime, but 91 is \(7 \times 13 \).

In the livestream chat the concept of primemirp emerged. This would be a concatenation of a prime with its emirp. There’s a niggle here: just like in the word ‘primemirp’ the ‘e’ is both the end of ‘prime’ and the start of ’emirp’, so too in the number the middle digit is end of the prime and the start of its emirp.

Why? Say the digits of a prime number are \( a_1 a_2 \dots a_n \), and its reversal \( a_n \dots a_2 a_1 \) is also a prime. Then the straight concatenation would be \( a_1 a_2 \dots a_n a_n \dots a_2 a_1 \). Each number \(a_i\) is in an even numbered place and an odd numbered place. Now, since

\[ 10^k \pmod{11} = \begin{cases}

10, & \text{if } k \text{ is even;}\\

1, & \text{otherwise,}

\end{cases} \]

it follows that each \(a_i \) contributes a multiple of eleven to the concatenation. A mismatched central digit breaks this pattern, allowing for the possibility of a prime.

I wrote some code to search for primemirps by finding primes, reversing them and checking whether they were emirps, then concatenating them and checking the concatenation. I found a few! Then I did what is perfectly natural to do when a sequence of integers appears in front of you – I put it into the OEIS search box.

Imagine my surprise to learn that the concept exists and is already included in the OEIS! It was added by Patrick De Geest in February 2000, based on an idea from G. L. Honaker, Jr. But there was no program code to find these primes and only the first 32 examples were given. I edited the entry to include a Python program to search for primemirps and added entries up to the 8,668th, which I believe is all primemirps where the underlying prime is less than ten million. My edits to the entry just went live at A054218: Palindromic primes of the form ‘primemirp’.

The 8,668th primemirp is 9,999,713,179,999.

Pythagorean triples have a long and storied tradition. But what about the near misses?

You’d be surprised how much math[s] you can learn by exploring some of the implications and ramifications of what may seem at first no more than a trivial brainteaser

Martin Gardner

A while ago, my son did the Prime Climb colouring sheet.

Eight years after Shinichi Mochizuki first posted his proof of the ABC Conjecture on his website it has been announced that it has been accepted for publication in Publications of the Research Institute for Mathematical Sciences (RIMS).