I’m a big fan of novelty domain names: I once bought hotmathematicians.com just so that christian@hotmathematicians.com could be my corresponding address when I submitted a paper. That domain has expired, but my love for one-shot novelty purchases has not!

To celebrate π day this year, I decided that it should be possible to type a little bit of π into the internet and be given the rest of it. You can have dots in domain names, so a domain like “three.something.com” is possible. I only know π to two decimal places off the top of my head, so I was dismayed to learn that onefour.com is being squatted.

After a bit of googling to find more digits of π (hey, this website will be really useful once I set it up!), I found the first decimal approximation which hasn’t already been registered:

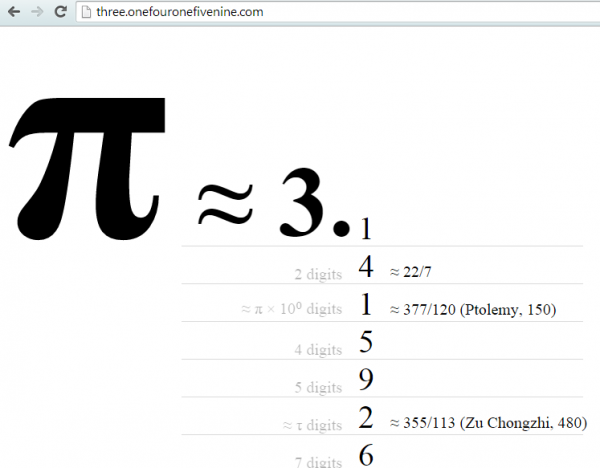

three.onefouronefivenine.com

Try going there now. It really exists!

I’ve set it up so you get an endlessly scrolling list of decimal digits of π, generated using my favourite unbounded spigot algorithm. I suppose you can consider this my entry in our π approximation challenge.

A good π day’s work.